White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus)

White-tailed deer are an iconic species in the Alberta countryside. They are shy and usually bolt when spotted, waving their characteristic white flag as they retreat and disappear into the trees.

Photo by Stephanie Weizenbach

Why they Matter to Us

Deer are an integral part of a healthy Albertan ecosystem, feeding on plants and serving as prey for many species.

White-tails are generally non-confrontational and a delight to glimpse in their natural habitat.

Early settlers and Native Americans used White-tailed deer hides to make buckskin leather.

They are still hunted today within regulations and used as meat and leather.

Shed antlers are commonly used as decorative pieces or as dog chews.

How You Can Help

Support protected areas in the Edmonton region (such as EALT!). You can donate or volunteer your time to help with conservation efforts. All of EALT's conserved lands are home to White-tailed deer.

Modify your barbed wire fence to meet wildlife friendly standards. This will ensure deer of all ages and condition can easily cross your fence. You can also volunteer to help EALT remove hazardous barbed wire from our natural areas to improve wildlife habitat.

Reduce the chance of a vehicle collision with deer using the following tips:

Use your high beams at night, when possible, to make the deer's eyes glow so you can see the deer well in advance.

Scan the road and ditches ahead for animals, especially when travelling at dawn or dusk.

Slow down around curves, and at the crest of a hill. Reduce your speed at night when driving on unfamiliar roads, or roads lined with trees.

If you see a deer crossing the road ahead of you, look for more deer following behind it - they often travel in groups.

Brake firmly if a deer runs out in front of the vehicle - avoid swerving.

Help keep fawns safe when they are first born, in early June:

Does hide their fawn in tall grass or shrubs when they are first born, to keep them safe from predators. The doe returns every few hours to feed and move the fawn. If you see a fawn laying in the grass, leave it alone, and keep your pets away from it - mom will be by shortly.

How to identify

Photo by Dawn Huczek

Identify by Sight

White-tailed deer get their name from their tail which has a white underside. When alarmed, they hold their tail upright - exposing the white - as they bound away.

Their body is reddish-brown in the summer, changing to greyish-brown in the winter.

Bucks have unbranched antlers with tines extending from single beams.

Unlike mule deer, white-tails have no rump patch

Identify by Sign

Bucks rub their antlers on trees for a number of reasons: rubbing off velvet, marking territory during rut, and shedding their antlers. Look for stripped bark still hanging off the tree.

Deer droppings are larger than rabbit feces and smaller than moose droppings.

Hoof prints are 7 - 9 cm long by 4.5 - 6.5 cm wide and look like two elongated tear drop shapes.

Deer are notorious for foraging continuously along the same pathway, so deer trails are well worn and easy to spot.

Deer beds can be found by noting flattened ovals in the snow or tall grasses.

Where to Find

White-tailed deer are one of the most widely distributed and numerous of all North America’s large animals. They are found in the prairie, parkland and southern boreal zones in Alberta and their range is expanding westward into the foothills, mountains and northward further into the boreal zone. Typical habitat includes aspen groves, and grasslands and fields near scattered patches of trees.

White-tailed fawn by Gerald Romanchuk

Fawn safely hiding at Golden Ranches

Social Life

White-tailed Buck by Gerald Romanchuk

In Alberta, the rut, or mating season, occurs in November. Males spar with rivals, battling each other with their antlers.

White-tailed deer are generally solitary in the summer and live in varying sizes of herds in the winter.

Food Chain

Abundant food makes almost any forested or bushy area suitable during the summer, while deer feed on leaves, branches, forbs, berries, and even lichens and fungi.

Surviving in the winter may be particularly difficult if there are too many deer competing for food or if the snow is too deep.

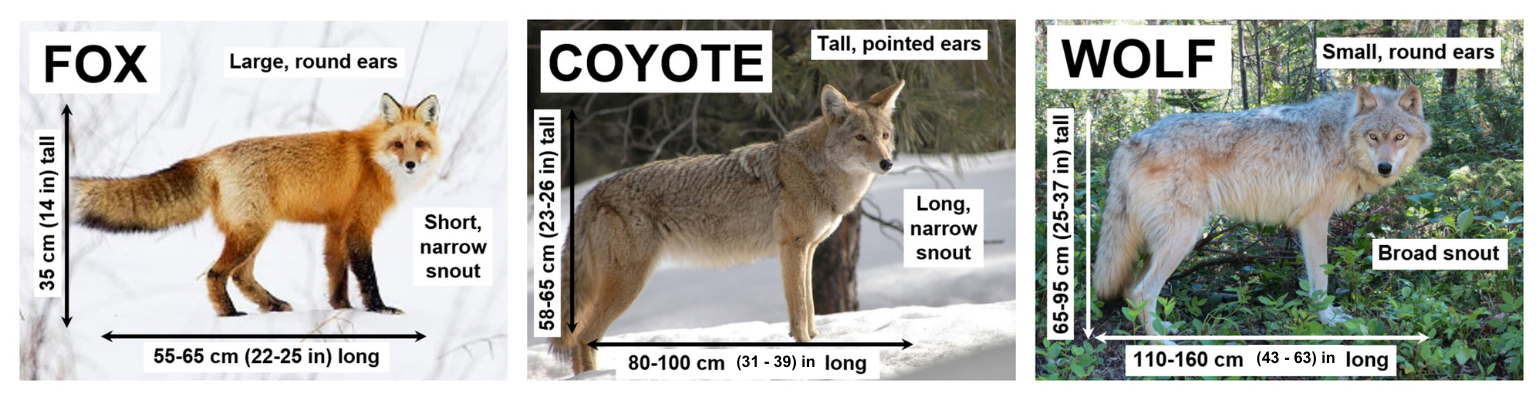

Deer (particularly fawns) are prey to many predators including: coyotes, wolves, cougars, etc.

Fun Facts

Bucks shed their antlers after the rut (approximately late February to March) and begin to regrow their antlers in the spring.

Fawns are born with white spots to help them camouflage. The spots emulate scattered light through a treed forest (sun/shade patterns created by leaf cover).

Deer have scent glands between the two parts of their hooves, and on their legs. These scent glands are used to communicate with other deer.